Findings

First findings of the representative survey 'Menschen in Deutschland 2022' (People in Germany 2022)

| The study "Menschen in Deutschland" (MiD) is conducted by the University of Hamburg as part of the nationwide research network MOTRA. It examines the opinions and attitudes of people aged 18 and over in Germany on political, social, and religious issues. To this end, an annually repeated, representative survey of the adult population throughout Germany is conducted since 2021, in which more than 4,000 people each year have their say on these topics. In the following, first results of the MiD study from 2022 (second wave) as well as changes in social and political attitudes compared to the first wave from 2021 are presented. |

People in Germany 2022 – Who are our participants?1

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| 1 All evaluations reported on here were carried out using weighted data. This ensures that the sample corresponds to the proportions of the adult population in Germany with regard to central characteristics. This means that the results can be regarded as representative and generalized to all adult residents of Germany. For more information on the weighting procedure used and on the size of individual subsamples, please refer to Research Report No. 6 on the second wave of the MiD study, which is available in German online on the website of the Chair of Criminology at the University of Hamburg. |

Concerns and uncertainty in light of social challenges and changes

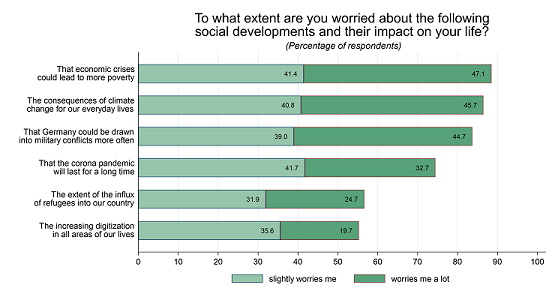

Worries and uncertainties were widespread among respondents in 2022. A large majority expressed concerns about the effects of current political and social developments such as impending economic crises, climate change, the Corona pandemic, or military conflicts.

In 2022, people were most concerned about economic crises and the threat of rising poverty. Almost half of respondents (47.1%) said they were "very concerned" about this, while another 41.4% were "somewhat concerned" about such developments. Concerns about the consequences of climate change were similarly high (86.5%), as was the concern that "Germany could be drawn into military conflicts more often" (83.7%). In contrast, just over half of respondents said they were "very" or "somewhat" concerned about increasing digitalization (55.3%) and the influx of refugees to Germany (56.6%).

The results for 2022 cannot be directly compared with those of the previous year due to changes in the formulation of the questions. Nevertheless, there is a noticeable tendency for the majority of respondents to remain concerned about current developments to a similarly high degree as in 2021 (for more information, see the brief results of the MiD 2021 study). In particular, the concern that Germany could be drawn into military conflicts more often has increased significantly compared with the previous year (from 70% to 83.7%), which was to be expected given the outbreak of the Ukraine war in the meantime.

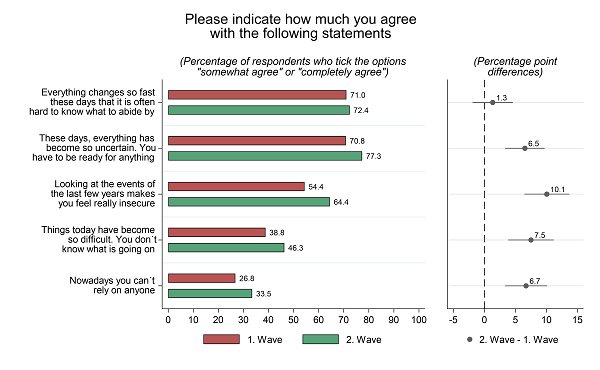

In addition to these specific challenges and concerns, a more general set of questions was also asked to determine how widespread feelings of insecurity due to social changes and innovations are among the population. As in 2021, the highest levels of agreement were found for statements about uncertainty due to rapid change (72.4%) and the feeling of having to be "ready for anything" (77.3%). While the percentage of agreement on the first statement is just as high in 2022 as in 2021, agreement on the second statement has increased by more than 6 percentage points. Increases were also seen for the statements that people become uncertain when they consider the events of recent years (from 54.4% to 64.4%) and the statement that things have become so difficult today that people "don't know what's going on" (from 38.8% to 46.3%).

On the other hand, the statement "Nowadays you can't rely on anyone anymore" was met with the least approval at 33.5%. Although this suggests a rather low level of insecurity in the area of personal social connections, there is nevertheless a clear increase of 6.7 percentage points in the rate of those who are insecure in this regard.

Overall, all statements thus received more approval than in the previous year. Current crises and changes that have occurred between the two surveys have thus triggered a general feeling of insecurity, which has increased significantly in some cases, and which in taken together affects more than half of the population.

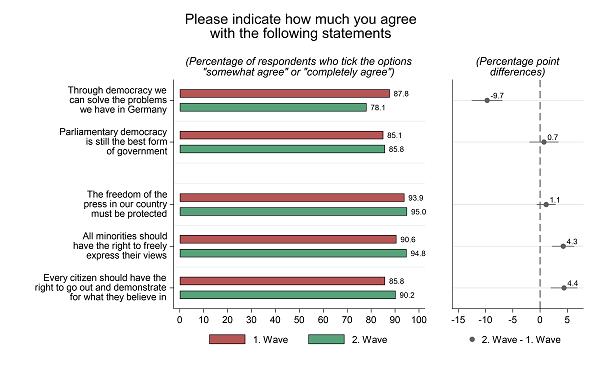

Evaluation of democracy and trust in politics

Democracy as the basis of the political system in Germany continues to enjoy broad approval among the population: 85.8% of respondents consider parliamentary democracy to be the best form of government. At the same time, however, significantly fewer people in 2022 than in 2021 believed that democracy could actually solve Germany's problems. Although a majority of 78.1% of respondents agreed with the statement, this approval rate fell by 9.7 percentage points compared with the previous year. Despite a very high level of general acceptance of democracy as a form of government, an increasing number of people thus doubt that it can solve current problems.

In contrast, acceptance of important fundamental rights and freedoms such as freedom of assembly ("Every citizen should have the right to go out and demonstrate for what they believe in"), freedom of expression ("All minorities should have the right to freely express their views") and freedom of the press ("The freedom of the press in our country must be protected") has somewhat increased. In particular, the positive evaluations of freedom of expression and freedom of assembly have each increased by more than 4 percentage points. Overall, all of the fundamental rights surveyed here experience very broad approval, with rates ranging from 90.2% to 95%.

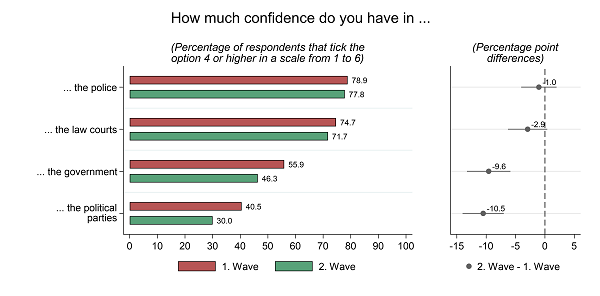

The noticeable increase in skepticism and doubts about democracy's ability to solve problems in the face of current challenges is also reflected in the data on trust in relevant political institutions.

Although the population's trust in the police and the courts remained high at 77.8% and 71.9%, respectively, trust in political actors was significantly lower: At 30% and 46.3% respectively, less than half of the people in Germany trusted the political parties and the government. Moreover, compared with the previous year, trust in 2022 fell by just under 10 percentage points in each of these respects, indicating a very considerable deterioration.

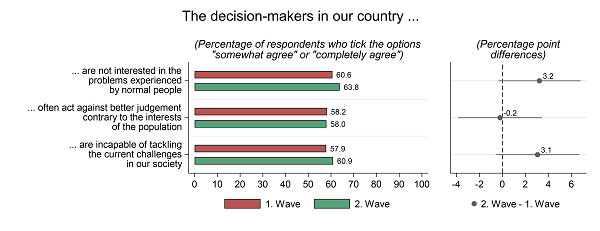

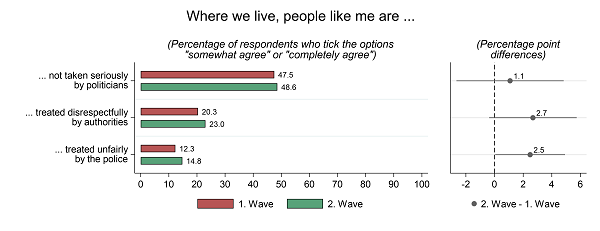

This clear decline in general trust in political institutions and actors is also reflected in the respondents' assessments and opinions regarding the motives and competencies of key decision-makers in politics, science and business. In this regard, the statement that these actors are "not interested in the problems experienced by normal people" received the most approval, at 63.8%. Likewise, significantly more than half of the respondents (60.9%) stated that decision-makers are "incapable of tackling the current challenges in our society."

The statement that they "often act against the interests of the population"2 received a similarly high level of approval (58%). Overall, the approval rates are in a similar range as in 2021, although the assumptions of lack of interest and inability to solve problems tend to increase.

| 2 The wording of this statement has changed slightly compared to 2021. There, the wording "...often act against better judgement contrary to the interests of the population" was used. |

Respondents were also asked to provide their perceptions about how people who are like themselves (i.e., who belong to their own social group) are treated by state institutions, regardless of their own experiences.

The focus here is on the subjective perception of respect, fairness and recognition on the part of representatives of politics and state authorities in direct contact with citizens. According to the findings of research on these topics, this perception has a high significance for the acceptance of these institutions and of social rules, values and laws represented by them. The experience of respect and fairness as well as genuine interest are decisive for how strongly people identify with our political system and feel that they belong and are recognized.

In this respect, similar to 2021, almost half (48.6%) of respondents stated that they felt that people like themselves were not taken seriously by politicians. The assessment of state authorities in general and the police in particular was better. Only 23% and 14.8%, respectively, perceived forms of disrespectful or unfair treatment. Compared to 2021, however, there was a small increase of slightly more than 2 percentage points in each case.

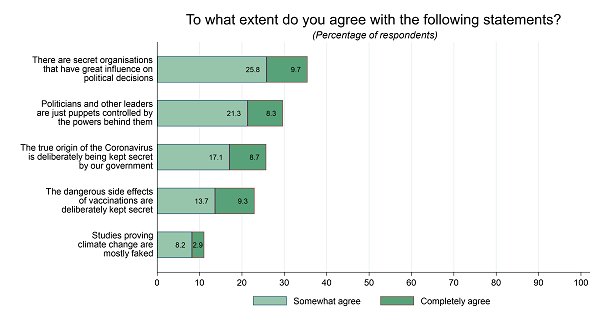

In 2022, the MiD survey recorded for the first time how widespread the tendency to accept conspiracy myths is, i.e., unverifiable assumptions that social events, situations or developments are controlled by secret powers. With an agreement of 35.5%, the assumption that "there are secret organizations that have a great influence on political decisions" was met with remarkably high approval. 29.6% also agreed with the statement that politicians and other personalities are "puppets controlled by the powers behind them."

Somewhat less widespread was agreement with specific conspiracy myths. About a quarter of respondents agreed with statements about the intentional hiding of the origin of the Corona virus (25.8%) and the dangerous side effects of vaccinations (23%). More than one in ten individuals (11.1%) also believed that "studies proving climate change are mostly faked."

Overall, the 2022 findings on the assessment of democracy, the state, and politics show that trust in political actors (government and parties) has fallen significantly compared with the previous year. This is accompanied by growing skepticism about democracy's ability to actually solve current problems. However, fundamental rights and freedoms are still viewed positively by the vast majority. State institutions in the administration of justice and law enforcement, such as the police and courts, also continue to enjoy a high level of trust and are viewed less critically than political actors in government and political parties. Overall, however, this acceptance and trust generally decreased in 2022 compared with the previous year.

The critical assessment of relevant decision-makers in politics and society also continues to show itself in the tendency to believe in conspiracies. In particular, the assumption that secret powers and organizations exert influence on political decision-makers affects only a minority of respondents but is nevertheless comparatively common: More than a quarter of the population tends to believe in conspiracy myths and thus to use simple explanations for difficult and threatening developments and problems in a situation of subjectively high uncertainty.

It can be assumed that these results show a network of reciprocal influences: A general distrust of actors from politics and science is connected with concerns about current crises and developments such as the Corona pandemic, climate change, or the war in Ukraine. This, in turn, is accompanied by increased insecurity and a rise in skepticism toward social and political decision-makers as well as toward democracy's ability to function and solve problems.

| Our study places one of its focal points on political and social conditions and their evaluation by the respondents. Only when people tell us about their experiences and observations, we can recognize what problems they perceive and how they assess them. Therefore, we ask our respondents about their own experiences with discrimination as well as observations in their own living environment that could indicate intolerance, prejudice and political extremism. This helps us to make statements about how widespread such situations and experiences are in Germany and to what extent people feel threatened by them. |

Personal experiences of discrimination

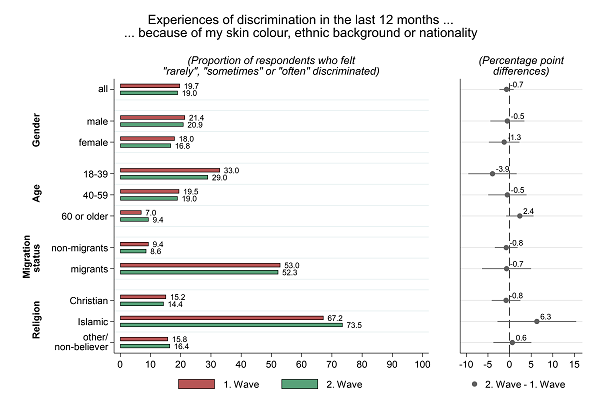

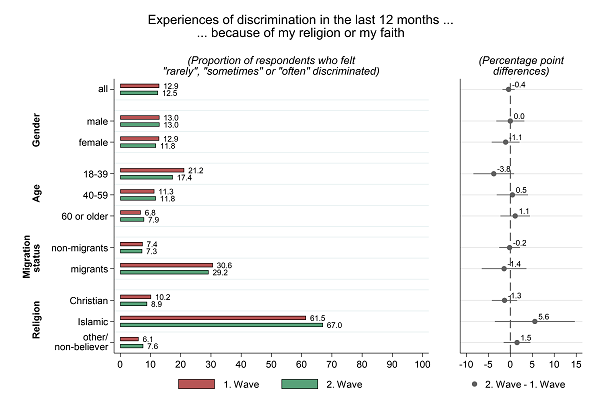

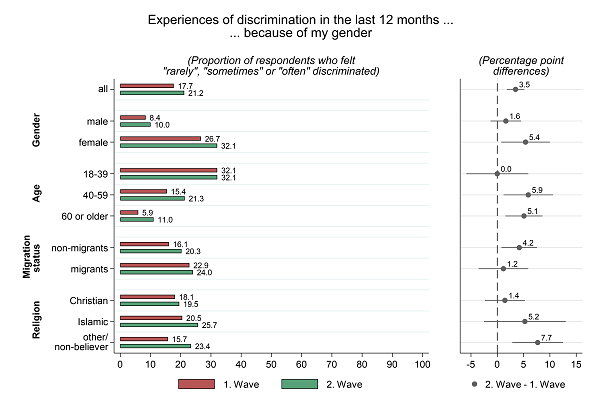

Overall, more than half of the respondents stated that they had personally experienced some form of discrimination in the last 12 months. However, there are considerable differences depending on the type of discrimination and the characteristics of the respondents (e.g., their age group, gender, migration background, or religious affiliation).

Discrimination on the basis of skin color, ethnic origin, or nationality was reported somewhat more frequently by men than by women and significantly more frequently by younger than by older people. Specifically, 29% of respondents under the age of 40 reported having been discriminated against on these grounds. For people aged 60 and over, the rate is only 9.4%.

It should be emphasized that people with an immigrant background (52.3%) and people of the Islamic faith have experienced such origin-based discrimination significantly more often in the past year than other people. In addition, it can be seen that such experiences especially tended to increase among Muslims in 2022, with an increase from 67.2% to 73.5%.

A similar pattern is found for the prevalence of discrimination on the grounds of religion or belief. These were also reported more frequently by younger individuals between the ages of 18 and 40. Such religion-related discrimination is clearly more common among people with a migration background (29.2%) and among Muslims (67%). For both groups, but especially for the latter, a high risk of multiple discrimination can therefore be assumed, which has also increased slightly in the last year - as was already observed with regard to origin-related discrimination.

The clearest differences compared to the previous year are evident for gender-related discrimination. Overall, 21.2% of respondents reported that they had been discriminated against on the basis of their gender, with this rate being significantly higher among women (32.1%) than among men (10%). Reports of such experiences of discrimination have each increased by more than 5 percentage points since 2021 for women, as well as for people aged 40 and older. A similar trend can also be observed for people without an immigrant background and for people with Islamic or no religious affiliation.

Overall, this means that in 2022 there are significantly more people, particularly among women, who report gender-based discrimination experiences. The development of the distribution across age groups indicates that the sensitivity to correspondingly problematic situations and thus the perception of gender discrimination has increased in particular among respondents aged 40 and above, which is likely to have contributed to the overall increase.

Perception of intolerance and political extremism in one's own living environment

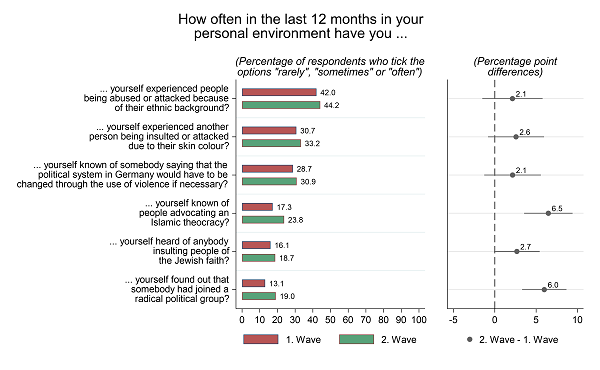

In addition to questions about their own experiences of discrimination, respondents were also asked to report perceptions of events in their social living environment that they had observed and that could be politically significant. Overall, such observations were reported slightly more frequently in 2022 than in the previous year. Most respondents (44.2%) said they had witnessed "people being insulted or attacked because of their ethnicity" at least rarely in the past 12 months. Just under one-third of respondents (33.2%) had themselves witnessed "another person being insulted or attacked because of their skin colour." Forms of xenophobia and racism thus continue to be a directly visible problem in the living environment of many respondents.

Indications of political extremism and radicalization processes were also perceived more frequently by respondents in 2022 than in 2021. Observations that other people have "advocated an Islamic theocracy" (23.8%) and "that someone had joined a radical political group" (19%) increased by 6.5 and 6 percentage points respectively in the past year. This is a first indication of an increased perception of cases of political extremism in the past year.

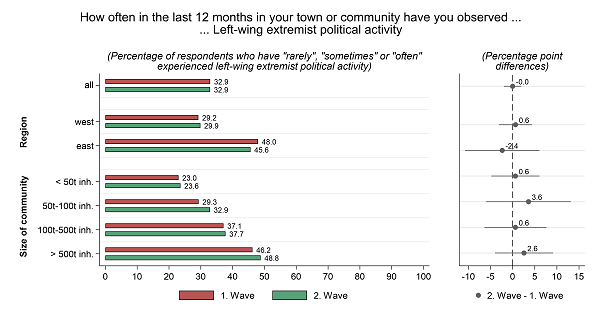

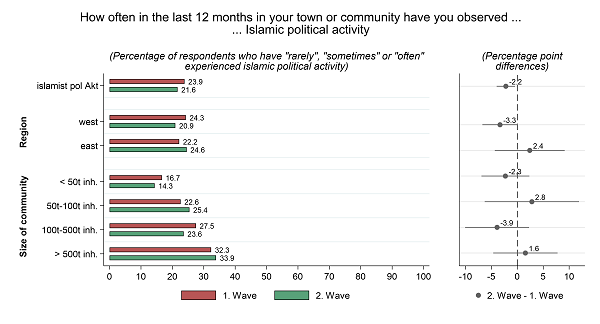

Respondents were also asked about their perceptions and observations of various political extremisms - in the form of left-wing extremist, right-wing extremist and Islamist activities - in their own living environment.

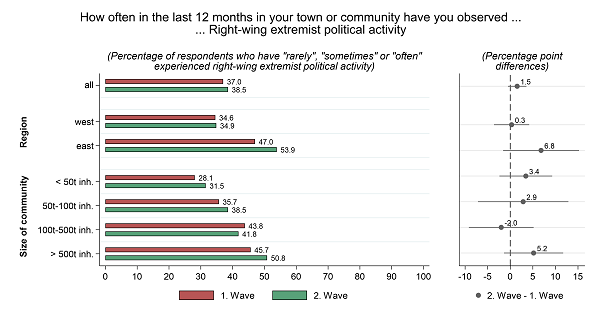

In this regard, right-wing extremist activities were observed most frequently (38.5%), followed by left-wing extremist activities (32.9%). Islamist activities were observed least frequently (21.6%). The extent of such perceptions has thus hardly changed compared to the previous year, although slightly fewer Islamist activities were reported by respondents.

A breakdown of the observation frequencies by regional characteristics shows that in medium-sized cities and large towns, the rates of those who have perceived such activities at least "rarely" are higher in each case than among respondents living in smaller towns. This was to be expected, however, since the higher population density in a large city compared to smaller places means that the opportunity to observe such activities is more frequent, and political protest events are generally more likely to take place in larger cities as well.

Another difference in observation frequencies is found in the east-west comparison, with both right-wing and left-wing extremist activities being observed significantly more frequently in the eastern states than in the western states. In the West, such observations were made by just under a third (29.9% and 34.9%, respectively) of the respondents, while in the East, this was expressed by about half of the respondents (45.6% and 53.9%, respectively). Right-wing extremist activities were observed significantly more frequently in the east in 2022 compared to 2021, while left-wing extremist activities tended to be less frequent.

Regarding Islamist extremism, the values fluctuate by up to +/- 4 percentage points compared to the previous year, depending on the regional location of the respondents. Thus, no clear trend can be discerned for any of the three extremist phenomena.

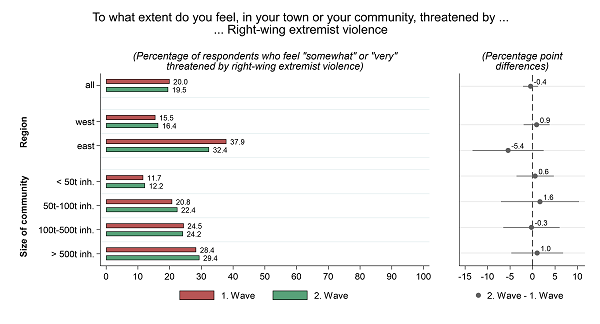

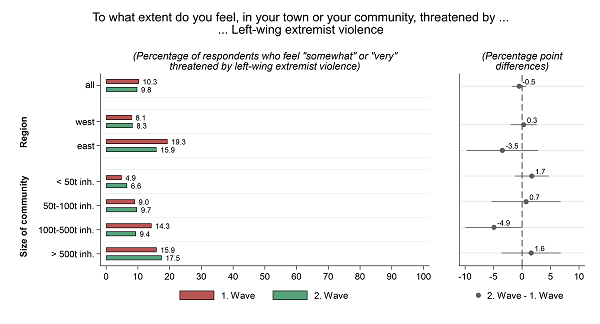

In addition to the frequency of purely observing politically extremist activities in one's own living environment, the survey also asked to what extent people personally feel threatened by politically motivated violence in their living environment.

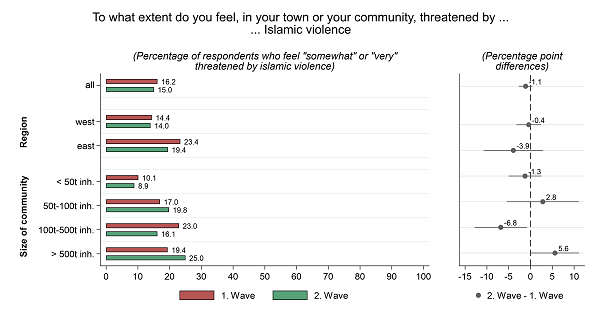

The highest sense of threat stems from right-wing extremist violence, which 19.5% of respondents felt somewhat or very threatened by in 2022. It is striking that the perceived threat by Islamist violence follows with a share of 15%, although observations of such activities were reported least frequently when comparing the three forms of extremism. Overall, however, the extent of the perceived threat is lower than the observation frequencies might suggest. Compared to the previous year, no changes can be noted here.

As with the observation of extremist activity, feelings of threat from political extremist violence also show that these are more frequent in large cities. Changes between 2022 and 2021 relate primarily to medium-sized large cities (100,000 to 500,000 inhabitants), where feelings of threat with regard to left-wing extremist and Islamist violence have decreased. In contrast, there is an increased rate of feelings of threat due to Islamist violence in large cities with over 500,000 inhabitants compared to the previous year.

These evaluations show that the development of the observation frequency of certain activities is not necessarily associated with a corresponding degree of threat perceptions. Rather, it can be assumed that other factors play a role here.

The aim of the "People in Germany" study is to identify precisely such factors and to show how social situations and their changes affect the lives of people in Germany.

An important topic here is, above all, the question of how people's assessment of politics and society will develop and potentially change over the course of the next few years, and how this will affect the spread of political extremism and the acceptance or rejection of our democracy. The surveys conducted as part of our "People in Germany" study will be continued on an ongoing basis in the coming years so that changes and their possible backgrounds can be made visible.

|

This brief report was intended to provide an initial insight into the questions and selected findings of our "People in Germany 2022" survey. We would also like to take this opportunity to sincerely thank all respondents for their time. Thank you for supporting us by participating in the survey! If you have any questions, please contact our team at the University of Hamburg at mid-studie"AT"uni-hamburg.de. |

First findings of the representative survey ‘Menschen in Deutschland 2021’ (People in Germany 2021)

| The study 'Menschen in Deutschland' (MiD) is a Hamburg University research project. It is part of the German-wide research network MOTRA funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and the Federal Ministry of the Interior and Community (BMI), in which research groups from 8 universities and research institutes cooperate. Central aim of MOTRA is the long-term observation and analysis of political radicalization processes and its particular manifestations in Germany. Within this research network, the MiD study examines people's opinions and attitudes on political, social, and religious topics. For this, repeated representative surveys of the adult population in Germany are conducted annually from 2021 onwards, in which more than 4,000 people will have their say on these issues. First results of the 2021 survey will be presented below. They show how people in Germany perceive important social and political matters. Furthermore, they provide information about the prevalence of certain politically relevant attitudes, and about how respondents judge specific social problems and current developments in our society. |

People in Germany 2021 – Who are our participants?1

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 All evaluations were carried out with weighted data. This ensures that the sample corresponds to the conditions of the adult population in Germany with regard to central socio-structural characteristics. This means that the results are representative and can be generalized to all adult inhabitants of Germany. Further information on the weighting method used and the size of individual sub-samples can be found in the “Forschungsbericht No. 2” to the MiD 2021 study, which is available online on the Hamburg University - Institute of Criminology website. |

Worries and uncertainties amid social challenges and changes

A large proportion of the respondents expressed concern about the impact of current developments such as the COVID-19 pandemic, looming economic crises, and climate change.

In spring 2021 people were most concerned about the COVID-19 pandemic. With 89%, the majority of respondents are “slightly” or “a lot” worried that the pandemic “will continue for a long time and could overwhelm the health system". Equally high was the level of concern that climate change "could increasingly lead to droughts, crop losses, and floods". 90% of respondents expressed their concern in that regard. A similar level of worry was also expressed with respect to economic crises and a potential increase in poverty in Germany.

More than two-thirds of people were also concerned that Germany could be drawn into military conflicts more often due to an increase in armed conflicts in the world, although comparatively few people (27%) expressed "great concern" in this regard. In view of the developments in Ukraine, it is to be expected that these concerns of the population recorded here could turn out differently in the second survey ‘Menschen in Deutschland 2022’.

Respondents were less concerned that the influx of refugees could lead to the collapse of our social systems, although these fears were still shared by more than half of the sample. It should be emphasised, however, that with 18% only a relatively small proportion of respondents expressed themselves as "very concerned" about this.

Beyond concerns with respect to this selection of specific social challenges and developments, feelings of insecurity and alienation in times of social changes were surveyed on a general level. Almost three quarters (72%) of respondents agreed with the statement "Today everything is changing so fast that you often don't know what to stick to". More than half of the respondents (54%) also stated that social developments and important events that took place during the last few years were accompanied with increased feelings of uncertainty. It can be assumed that these two statements are largely related to the COVID-19 pandemic and the concomitant short-term changes in political measures and social rules in Germany. However, they also point to a general uncertainty caused by rapid and far-reaching multidimensional changes in society and politics.

In contrast, significantly fewer people - although still a substantial proportion at over a quarter of respondents - agreed with the statement "Nowadays you can't rely on anyone". Thus, social connectedness or feelings of trust in other people seems to be impaired only in a smaller proportion of people compared to the other worries, concerns and insecurities described above.

If we look at the average uncertainty, using a scale based on all five questions we asked the participants on this topic, a high degree of such generalized uncertainty is found in 20% of all respondents. Younger people under 30 (23%) and older people over 70 (27%) show the highest rates.

Assessment of democracy and trust in politics

Democracy as the basis of the political system in Germany enjoys a broad approval among the population. Between 85% and 90% of the respondents agreed with the corresponding statements that named democracy as the best form of government and as suitable for solving problems in Germany. Fundamental rights and liberties such as freedom of assembly ("Every citizen should have the right to go out and demonstrate for what they believe in"), freedom of opinion ("All minorities should have the right to freely express their views“), and freedom of the press ("The freedom of the press in our country must be protected") were considered worthy of protection by 86% to 94% of respondents and to that extent were rated very positively.

However, this positive picture with regard to the normative basis of the democratic constitution is only partially confirmed when looking at the confidence of respondents in relevant political institutions. While the trust in executive state institutions like the police and the courts was very high at 79% and 75%, respectively, the respondents' trust in political actors, i.e., the government and political parties, was significantly lower. Only slightly more than half of the respondents expressed trust in the government. Trust in political parties was even lower at only 41%.

The evaluation and assessment of decision makers from politics, science, and economy with respect to their motivation to act and their competences to deal with social challenges further confirm this lack of trust and confidence among many people. More than half of the respondents (58% each) stated that decision-makers often acted "against better judgement contrary to the interests of the population" and were “incapable of tackling the current challenges in our society”. With 61%, the highest level of agreement was registered for the statement that decision-makers were not "interested in the problems experienced by normal people".

Additionally, almost half of the respondents (48%) stated that they felt that people like themselves were “not taken seriously by politicians”. As before, the assessment of state institutions, authorities and the police was much better. Only 21% agreed with the statement that people like themselves are “treated disrespectfully by authorities”, and a minority of 12% think that people like themselves are “treated unfairly by the police”.

In other words, citizens tend to criticize specific political actors (i.e., government and parties), not so much the democratic system in general or state institutions with which respondents actually come into contact in everyday life (i.e., administrative authorities, police, and courts). It becomes apparent that not only the general trust in political actors is low among the population, but that large parts of the population do not trust relevant decision-makers and that their ability to cope with current challenges is seen with great doubts. Furthermore, a majority of respondents attribute politicians and decision makers a lack of interest in the problems of the population or even a willingness to act in ways that are explicitly contrary to the interests of the general population.

| Our study puts a major focus on political and social conditions and their evaluation by the respondents. Only when people tell us what their experiences and observations are, we can see what problems they perceive and how they judge these problems. Therefore, we ask our participants about personal experiences with discrimination on the one hand and about observations of a variety of situations in their living environment that indicate intolerance, prejudice, and political extremism on the other hand. This helps us to find out how common such situations and experiences are throughout Germany and to what extent people feel threatened by them. |

Personal experiences with discrimination and intolerance

In general, more than half of the respondents reported personal experiences with some form of discrimination in the last 12 months. However, strong differences were found depending on the type of discrimination and the age of the respondents. For example, of those under 40 years of age, 33% said they had been discriminated against because of their skin color, ethnic origin, or nationality. A comparably high proportion of this age group reported gender-based discrimination. 21% of the respondents in this age group reported being discriminated against due to their faith or religion.

Experiences of personal discrimination were significantly less frequent among people aged 60 years or older. Among those elderly respondents the rate of those who felt discriminated against varied between 6% and 7%. The discrimination rates among people aged 40 to 59 lie in the middle of the three age groups.

Percentage of respondents who have "rarely", "sometimes" or "often" felt discriminated against.

However, these results do not point to a generally more frequent discrimination of younger people. The results may also indicate a different perception of discriminatory behavior by younger people, who may be more aware and sensitive to such problematic situations. Additionally, the forms of discrimination surveyed here are only a limited selection of possible forms of disadvantage and discrimination in everyday life. For example, they did not include experiences of age-related discrimination where different results might be expected.

Perception of intolerance and political extremism in own living environments

In addition to questions about their own experiences with discrimination, respondents were asked to report their observations and perceptions of forms of political extremism and intolerance in their neighborhoods and their larger social and personal environments.

Overall, the observation of various forms of discrimination, prejudice and intolerance towards others was reported more frequently than own personal experiences of discrimination. For example, 42% of respondents said they had witnessed other people being insulted or attacked because of their ethnic origin in the last 12 months. Almost one third (31%) of the respondents observed another person being insulted or attacked because of their skin color. This shows that many respondents are directly and personally confronted with forms of xenophobia and racism in their everyday lives.

Observations indicating antisemitism were made with varying frequency depending on their form of appearance. While almost half of the respondents (45%) had seen antisemitic graffiti or slogans in their personal environment during the last 12 months, only 16% said that they had personally witnessed an insult against people of the Jewish faith during this time.

Those types of actions can be a contributing factor for the development of extremist attitudes and activities; however, they may not inevitably be interpreted as a component of extremism by respondents. Thus, respondents were further asked about their perceptions and observations of various forms of political extremism, i.e., left-wing extremist, right-wing extremist and Islamist activities, in their living environments.

Right-wing extremist activities were observed most frequently: 15% of the respondents stated that they had observed such activities "sometimes" or "often". At 13%, the rate of observations of activities attributed to the left-wing extremist spectrum was only slightly lower. Islamist activities were observed least often (8%).

Strong differences in the frequency of such observations become apparent when looking at the size of the respondents' place of residence. For all forms of extremism, the proportion of respondents who have perceived such activities is higher in large and medium cities. Left-wing and right-wing extremist activities in large cities were observed "sometimes" or "often" by slightly less than a quarter of the respondents, while Islamist activities were observed by only 11%.

These distributions correspond to expected differences, assuming that the higher population density in large cities increases the opportunity to observe such activities, compared to the situation in smaller communities. In addition, protest events are usually more frequent there, which can lead to corresponding political statements and activities.

Considering the rates of such observations separately for the 16 German states, clear differences within Germany become apparent - shown here using the observation of right-wing extremist activities as an example.

At first glance, the proportion of respondents who have observed right-wing extremist activities "sometimes" or "often" exceeds the German-wide average of 15% in Brandenburg (24%), Saxony (26%), and Thuringia (22%). However, this phenomenon does not only affect the new eastern states of Germany, which is shown by even higher rates in the city-states of Berlin (35%) and Bremen (28%). At the same time, however, Hamburg, also a city state, has the lowest rate with only 7%.

These results show that simplistic explanations, e.g., based solely on the size of the place of residence or the region in Germany, do not do the complexity of such phenomena justice. Our further research will therefore also focus on investigating the reasons for regional differences in perceptions of extremist activities more nuanced.

In addition to the prevalence of political extremist activities, feelings of threat that are triggered by forms of politically motivated violence are a relevant factor in assessing the perceptions of respondents regarding extremism in Germany. The extent of such subjective feelings of threat was, on average, somewhat higher than the frequency of the corresponding observations. Here, too, the highest values were recorded in the area of right-wing extremism (20%). However, it is notable that despite the more frequent observation of left-wing extremist activities described above, the perception of threat from left-wing extremist violence (10%) was significantly lower than the perception of threat from Islamist violence (16%).

As was already the case with the observation of extremist activities, it is evident here that in larger places of residence and especially in large cities, feelings of threat from these three forms of extremist violence are more widespread (16% to 28%) than in smaller locations.

These first analyses show that the observation of activities that point to intolerance, hate or extremism does not necessarily have a direct effect on the perception of threats or concerns. Rather, it can be assumed that additional factors (e.g., representations of certain activities or situations in the media) become relevant here. This applies not only to political forms of extremism, but also to the perception and personal relevance of broader social problems and the evaluation of political and societal actors, as shown above.

The aim of the study ‘Menschen in Deutschland’ is to identify such factors and to show how social situations and their changes affect the lives of people in Germany. Furthermore, the study pursues the question of how perceptions and subjective assessments of politics and society will develop in the coming years. For this purpose, the MiD surveys will be conducted repeatedly every year starting in 2021, so that changes can be made visible, and their possible backgrounds can be examined.

|

This short report provided a first insight into the research questions and selected findings of our survey ‘Menschen in Deutschland 2021’. We would like to sincerely thank all respondents for their efforts and their time. Thank you for your support by participating in the survey! If you have any questions, please contact our team at the University of Hamburg via |